Belen Cocke

Guest Writer

It’s April 24, 2013. A normal day in Dhaka, Bangladesh.Women, men, and children make their way to work, most commonly in the textile factories. Textile production moved to Asia in the 1970’s, where labor costs were next to nothing and clothing could be made exponentially faster than in the United States. As countries like China, India, and Vietnam began to urbanize, an influx of jobs drew people from their subsistence farming lifestyles to large cities such as Shaoxing or Jaipur, and the cycle began to take place: cheap labor, fast production, clothing shipped to overseas shopping malls. Production then moved to Bangladesh (where labor was astonishingly cheaper) in the 1990’s, where large multinational corporations could take advantage of an abundance of labor at low costs.

After failing to act on the employees’ complaints of structural flaws and instabilities, the Rana Plaza conglomerate building in Dhaka, where thou- sands worked to support their families, collapsed, killing 1,134 people. The Rana Plaza building was not supposed to house textile factories, only apartments and shops. But money talks, and corporations such as Benetton andWalmart were among the many brands taking advantage of cheap labor in the developing world and producing goods in Rana Plaza.

The unfortunate and unnecessary deaths at the Rana Plaza factory served as eye-opener for the world.Who is making our clothes? And for what cost?

Fast fashion is defined by goodonyou.eco as “cheap, trendy clothing, that samples ideas from the catwalk or celebrity culture and turns them into garments in high street stores at breakneck speed.” Brands like Forever 21, H&M, Zara, Urban Outfitters, Charlotte Russe, and so many more, can be categorized as fast fashion brands. Every week, sometimes even multiple times a week, a completely new collection is found in the stores.This appeals to the consumer: gone are the days of entering a store, only to find the same boring old styles and cuts that are “oh- so-last-season.” In the world of fast fashion, there is no Spring/ Summer and Fall/ Winter; there are 52 seasons, one for each week, and the consumer ought to catch up.

So, what is the issue with fast fashion? Primarily, the ethics. Here’s an example: You enter H&M, and you’re looking for a new pair of jeans. Alas! They’re on sale. And for $15! You grab the pair and purchase, and they look great for the party the next week- end. However, after a couple of washes, the jeans begin to sag, fade, and tear. You throw them out—a shame, because you just bought them 2 months ago. Sound familiar? It shouldn’t be, but this is just one example of the vicious cycle fast fashion has on us as consumers. Cheap, low-quality, expendable clothes that spend a fraction of time in a closet, only to be thrown out when they deteriorate.

To be able to manufacture a $15 pair of jeans, and still manage a prof- it, is a terrible humanitarian crisis. Not only does this equate to a lower quality item, but it means that the company selling the jeans are paying the workers to manufacture them for about 1-2% of the final selling price an hour ($0.15-$0.30) according to Washington Post, and assuming this is occuring in Bangladesh, where most fast fashion production exists, this is still vastly underpaying the workers (minimum wage was set to $65 a week in Bangladesh in 2014 as reported by Bd News 24; whereas, someone working for $0.30 an hour, 12 hours a day, 6 days a week, is only making $21.60). The only possible way to be able to pay workers a living wage would be to increase the price of the garments, which most consumers would have to adjust to, and would decrease business. So, companies like Zara, H&M, and Forever 21 keep prices low, whilst keeping quality low and ethics at the bare minimum.

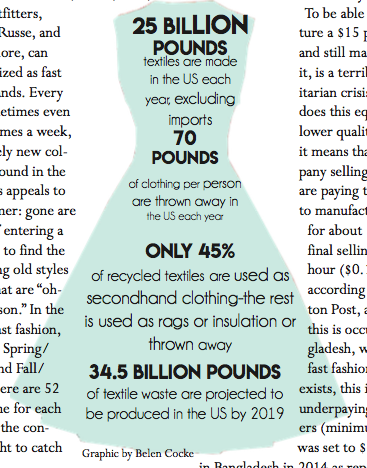

Not only is fast fashion an ethical dilemma, it’s an environmental one too. According to EcoWatch in 2015, Fast Fashion is the second “dirtiest” industry on Earth, right after Big Oil.The reason for this is that the materials used in the fast fashion industry have to be cheap and disposable, so synthetic fibers such as acrylic (substitute for wool) and polyester (substitute for cotton) are manufactured and shipped to the United States, Canada, Europe, and Australia and sold for dirt cheap, where they are worn a few times, then most likely thrown away or put in a charity bin.The problem is that, because the synthetic fibers are not naturally occuring, they don’t decompose well, and can take tens of thousands of years to leave the Earth, much longer than the week they spent in a mall. In addition, many of the dyes used in the clothing are cheap, and thus heavily toxic, and make their way into streams and oceans, furthering our pollution epidemic.

Fast fashion is a horrendous problem, and can only be stopped once consumers halt the demand for cheap, easy cloth- ing.The simplest way to avoid this toxic industry is to simply boycott: refuse to shop at stores that are not producing their garments ethically and sustainably, and instead shop at second hand stores or with companies that are transparent about their production process, such as Patagonia, Reformation, and Everlane. To quit fast fashion is a massive endeavor, one that will take practice and strong will—but it can be done, as long as one remembers the horrors behind the $10 sweater at the shopping mall.